Settlement

We can only guess at when and whence the first settlers came to this area. Generations gone by would tell that the first settlers in Lungiarü were the sylphs and the water nymphs, which takes us well into the realms of mythology.

*Archaeological finds * indicate that settlement of the Campill Valley began around 7,000 BC. In the summer months hunters and gatherers would come to the meadows beneath the Pütia/Peitlerkofel where the remains of stone tools have been discovered, made from materials which came from the Lessinia mountains near Verona and from Monte Baldo. The first signs of people who passed through the valley or settled in Lungiarü include a bronze fibula of a rider which was cast in Roman times, and an earring. It is difficult to estimate how many people settled here in Roman times; a large number probably arrived only during the time of migration from the Eisack Valley over the Würzjoch and Kreuzjoch passes or from the Pustertal Valley.

The last wave of immigration took place around the year 1000, a period when landowners were promoting the colonisation of the valleys in order to increase both agricultural yield and the population. The first surviving written documents with descriptions of borders also date to this time. In the year 1027 the village of Lungiarü, together with the orographic left-hand side of the lower Gadertal valley, were under the administration of the bishop of Brixen.

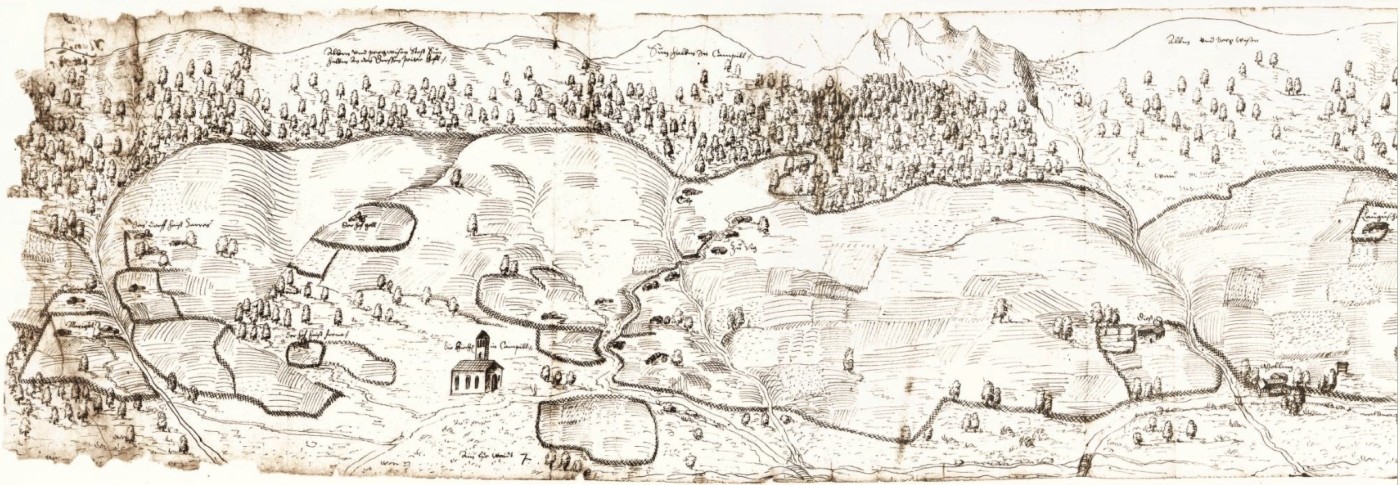

The bishop of Brixen was not solely the ecclesiastical authority of the area, but also the landowner and judge. The possessions of the Bishopric in the Campill Valley were managed by a caretaker in Thurn until 1803. A drawing dating to 1580 has been preserved which clearly illustrates the extensive clearances of this period: On the south-facing slopes around the village, fields and pastures were created, and separated from the higher-lying forestland and mountain pastures. Field names deriving from the root-word “runcé”(< lat. runcare = clear) such as Plan da Runch, Chi Runc, Runciadücia bear living testimony to the clearance work of the times. Alongside general land improvements, deforestation of woodland was carried out in order to put the most favourable areas to practical use. Documented references to farm names in the 14th century such as Col de Tolp, Corona, Costa, Seres und Tlisöra would suggest that there were stable settlements in this period. The Tolp farm above the village of Vi is generally considered by locals to be the oldest settlement of Lungiarü.

The first certain reference to the village dates back to 1312 with the name “Campil,” probably pronounced “Ciampëil,” today “Ciampëi.” The name “Lungiarü,” on the other hand, did not appear in documents from 1831, which does not preclude the fact that the inhabitants had not used this name beforehand. In 1349, we see also the first mention of a landlady, a certain “Elspet” (Elizabeth), landlady of Simons in Campill. Going by the parish chronicles, the first guesthouse was located at the site of the present-day Ostì Vedl” (Old Host).

As a result of the secularisation of administration and jurisdiction in the 19th century, the property of the Bishopric of Brixen finally came under the legal ownership of the state. The villages of San Martin de Tor with Picolin, Lungiarü, Antermëia and Rina, which had previously formed the Thurn an der Gader court, joined together in one single municipality. In 1854, Lungiarü and Rina broke off from San Martin de Tor, forming their own community. In 1930, Lungiarü joined with San Martin de Tor/St. Martin in Thurn once again and Rina came under the community of Mareo/Enneberg.

Catastrophes

In addition to the wars, epidemics and droughts which caused countless deaths and dire emergencies, Lungiarü also fell victim to a number of severe weather catastrophes. Over 500 years ago, in 1490, the first church – and, no doubt, a large part of the village along with it – were destroyed by a mudslide, while 100 and 45 years ago, floods and mudslides wreaked endless damage on fields and buildings. During the snow storms of 1916/17, 1951 and 1986, large avalanches destroyed buildings and entire hamlets were at risk of annihilation. In 1942, a tavern and several homes and farms went up in flames during the great fire in the village centre, and the entire village centre was in grave peril of the same fate.