According to the chronological tables of the Matsch village church, the Matsch valley was populated in far-back antiquity by Illyrian tribes. In 400 BC, it is said that the Celts arrived and, in coming together with the indigenous people of the valley, merged into the Rhaetian people. A Celtic helmet found in the Saldurbach River and the names of the Celtic deities “Eisa” and “Rumla,” which can still be seen in the names of fields today, bear witness to these times.

The name Matsch probably dates back to the pre-Roman-Indo-European adjective “mak” (damp, wet), which was extended to “makjā” (wetland). In the Alpine Romanesque this became “matšja,” while the name was transformed and “umlauted” in Middle High German to “Mätsche” (document from 1302). The interpretation of Matsch as the name of the “Valle amatsja” (happy, friendly valley), by the Romans who came here in around 15 BC corresponds to a folk-vision of etymology. The form “Amatia” dates back to the Romance “a Matšja” (on, in Matsch).

It is believed that the valley already served as a retreat for locals at the time of the Migration Period. “Amatia-Venosta” was documented as early as circa 824 AD, and numerous early medieval place names (Quadras, Pardeng) suggest that the Matsch valley was already permanently settled at this time, unlike the other side valleys of the Vinschgau, uninhabited until the high and late Middle Ages.

According to parish chronicles, in around 1200 there were already about a hundred families in Matsch. At this time, the aristocratic family of the same name settled in the valley, speeding up the settlement process; the Runhöfe farms would have come into being at this time as clearings.

Plagued by catastrophe

In the centuries to follow Matsch was ravaged by all manner of catastrophe. One particularly hard-hitting blow was the plague of 1348, when five-sixths of the population reportedly fell victim to the plague, which devastated the area once again in 1635. Today’s customary Way of the Cross on May 1, to the St. Peter Church in Tanas, dates back to these times when the saint was called upon to lift the curse.

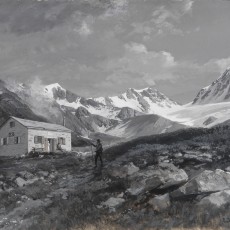

In 1613, an eruption beneath a glacier lake caused a devastating flood, an incident which was to reoccur in July 1737: “The common people of Matsch have been put in a position of misery and poverty so abject that their great misery cannot be described,” reported Kaspar Graf Trapp in a testimonial after the “Great Earthquake.” Water disasters plagued the valley time and again, and climatic changes and glacier growth (!) made the Saldurseen Lakes such an unpredictable force that flood barriers had to be constructed, but still the water sought its way out. The threat lessened only after the beginnings of glacial retreat. Incessant heavy rains coupled with periods of drought repeatedly led the “Matschers” to the brink of extinction and many were forced to emigrate in the 1880s – even as far as America.

The catastrophic weather of 1983 is remembered clearly by many Matsch people today: it rained for 72 hours without let-up, mudslides were triggered and even a part of the cemetery precipitated, along with its gravestones. Time and again the village has also been all but devastated by raging fires. A fresco on a barn in the upper village reminds us of the episode to this day.

It was not until 1927 that Matsch lost its status as an independent municipality and was integrated into the large community of Mals as a “fraction.” The population was expanding rapidly at this time, potato cultivation was introduced, livestock farming consolidated and settlement promoted. Mechanisation in agriculture also made its way to Matsch; artificial irrigation pipes were built, and the farmers’ work was eased somewhat. At this time, new jobs were also created in the Vinschgau in the industry sector.